The Clearinghouse System: A Production-Anchored Monetary Framework

______________________________________________

Abstract

Modern economies are stuck in a structural feedback loop: credit creates money, repayment destroys it, and governments are forced to keep printing to prevent collapse. Every “solution”—from quantitative easing to zero-interest lending—tries to patch liquidity instead of fixing its cause.

The Clearinghouse model replaces debt-issued money with production-issued money. Currency is minted when verified value is created and destroyed when that value is consumed. Real output, not leverage, becomes the driver of liquidity. This paper describes how the system functions, how it integrates with existing fiat frameworks, and why it resolves the chronic contradictions of debt finance without shocks, austerity, or utopian assumptions.

Introduction

Modern economies rely on debt to create money.

Every dollar in circulation originates as a loan that must be repaid with interest, which means the system constantly requires new borrowing to sustain itself.

This creates an inescapable imbalance: liquidity depends on leverage, and stability depends on perpetual expansion.

When credit creation slows, liquidity evaporates, and productive activity stalls—not because society has lost the ability to produce, but because it has lost the ability to account for that production.

The Clearinghouse System replaces debt-based money with production-based money.

Instead of being issued through loans, currency is minted and destroyed automatically as goods and services are exchanged.

Each verified transaction—whether labor, commodities, or finished products—creates new currency equal to the verified value sold, while the buyer’s payment destroys the same amount.

The money supply therefore expands and contracts in real time with production and consumption, maintaining equilibrium without central intervention.

Verification occurs through existing commercial signals: payroll logs for labor, certificates of analysis for commodities, bills of lading for shipments, and receipts for retail sales.

Complex transactions can include optional third-party verification, while everyday purchases operate on trust, just as they do now.

The result is a seamless digital and physical payment system that integrates directly into normal commerce—a networked marketplace, payroll processor, and accounting layer that measures the economy as it functions.

Because currency creation follows verified production, the Clearinghouse eliminates the structural imbalances of debt-based finance.

Inflationary bubbles, trade deficits, and wealth concentration arise only when money creation becomes detached from real output; this system mathematically prevents that detachment.

Efficiency and innovation become the direct sources of monetary expansion: every improvement in productivity literally grows the money supply.

On a global scale, this model aligns trade and reserves with real production rather than financial leverage.

Currencies strengthen as nations produce verified value and weaken when they consume more than they create.

International exchange becomes self-balancing, ending the dependency of debtor and creditor nations alike.

The Clearinghouse System is not a new currency—it is a new architecture for money itself.

It converts the act of trade into the act of measurement, creating a transparent, self-correcting monetary foundation where value, liquidity, and production remain perfectly aligned.

2 — Background: The Mechanics of the Debt Trap

2.1 How money is born and dies

When a commercial bank issues a loan, it simultaneously records an asset (the loan) and a liability (the customer’s deposit). The borrower spends that deposit into circulation. The instant the loan is repaid, both entries vanish. Money is destroyed. Every dollar, euro, or yen in use today was once created this way—backed not by goods, but by an IOU.

This logic makes perpetual growth a mathematical necessity. If everyone tried to pay off debt at once, the circulating supply of money would implode. The economy depends on continuous borrowing just to keep the books balanced.

2.2 The policy illusion

Governments and central banks compensate through liquidity injections—lower interest rates, quantitative easing (QE), and deficit spending. These create reserves or government debt that masquerades as new wealth but is really new obligation. The fresh liquidity flows first into financial assets, not wages or factories, inflating paper valuations while leaving real productivity flat.

The pattern repeats:

- Private credit expands until borrowers choke.

- The central bank intervenes, buying bonds and pushing rates lower.

- Asset owners get richer; productive sectors stagnate.

- Eventually, the system demands another rescue.

QE has become a life-support system for the accounting framework itself. It keeps markets liquid but starves the real economy of signal. No one can tell whether value is rising or merely leverage.

2.3 The Catch-22

The economy now faces two opposing pressures:

- It needs more dollars to service old debt.

- It cannot safely create them without adding even more debt.

This is the monetary equivalent of an engine that burns its own oil for fuel. Every “fix”—from negative rates to stimulus checks—just speeds up the depletion. What’s missing is a way to create liquidity that represents output, not obligation.

3 — Conceptual Break: Value as the Base Asset

The Clearinghouse approach starts from a first principle:

Currency should appear only when verified value is created and disappear only when that value is consumed.

Instead of central banks guessing how much money the economy “needs,” supply expands and contracts in direct sync with production and consumption. Verification replaces speculation. A ton of steel, a truckload of corn, a week of skilled labor—each becomes a measurable event that can mint currency into existence. When the good is sold or used, that currency is destroyed.

Where debt money is created before production and destroyed after repayment, Clearinghouse money is created during production and destroyed during use. Liquidity arises naturally inside the real economy, not outside it.

3.1 — Value Creation as a Self-Verifying Process

In the Clearinghouse model, value creation is tautologically true.

A transaction only occurs when two independent parties agree that value exists.

The buyer demonstrates willingness to sacrifice purchasing power; the seller demonstrates the ability to produce something worthy of that sacrifice.

That dual consent forms an intrinsic verification loop—an economic two-factor authentication.

Traditional money systems rely on external judgment: regulators, auditors, or lenders deciding what should be financed in advance.

The Clearinghouse flips that logic.

Verification happens at the moment of exchange itself, not by decree but by voluntary agreement.

If no one is willing to pay, the event never registers; no CHUs are minted.

If payment occurs, the existence of value is already proven by action.

This gives the system a kind of tautological integrity:

creation requires proof of demand, and demand requires proof of supply.

Each trade authenticates itself from both sides.

There is no theoretical debate about what counts as productive—the marketplace decides in real time through verified exchange.

Because of this, the Clearinghouse can measure value without philosophy or politics.

It doesn’t assign worth; it records consensus.

Money creation becomes an empirical statement: value exists because someone demonstrably valued it enough to trade for it.

That circular truth keeps the entire system grounded in reality while remaining fully decentralized in judgment.

3.2 — The Verification Spectrum and Opt-Out Flexibility

Verification in the Clearinghouse is not one-size-fits-all; it scales naturally with the complexity and variability of what is being sold.

At one end are high-variance or safety-critical goods—things like agricultural products, raw materials, or food ingredients—where independent certification adds genuine trust.

At the other are commoditized consumer goods, where quality and authenticity are already universally recognized.

Labor

For labor, verification is built into existing payroll mechanics.

A timeclock, contract log, or salary schedule is sufficient proof that work occurred.

When a worker clocks out or a salary period ends, the labor is automatically recognized as completed production, and CHUs are minted to represent that value.

Commodities

For raw commodities—corn, steel, crude oil, lithium—the process resembles current industry practice.

A licensed laboratory or inspection agency issues a Certificate of Analysis (COA) verifying quantity, grade, and purity.

That COA becomes the verification event that triggers CHU minting.

Manufactured Goods

As goods become more standardized, formal verification gives way to chain-of-custody confirmation.

In manufacturing and logistics, the bill of lading or delivery confirmation serves as proof:

“Yes, four pallets of bottled water arrived, and I signed for them after unloading them with a pallet jack.”

That acknowledgment is the verification moment.

Retail Transactions

At the consumer end, verification becomes nearly frictionless.

A point-of-sale receipt, invoice, or digital payment record is enough.

When a customer buys a bottle of Coca-Cola or a bag of Doritos, society already treats those as standardized, trusted goods.

The receipt itself functions as both proof of value and consumption.

Opt-Out Option

Participants can always choose to waive third-party verification for trusted counterparties.

If two businesses have a standing relationship and agree that verification costs outweigh the risk, they can trade on mutual trust.

The Clearinghouse records the transaction as self-verified and tags it accordingly.

This preserves efficiency while maintaining a paper trail for audits or disputes.

In short, verification is proportional to uncertainty.

When the product is variable or safety-critical, labs or inspectors handle it.

When it’s simple, observable, or standardized, acknowledgment or a receipt is enough.

3.3 — Services, Efficiency, and Net Money Growth

In the Clearinghouse system, services are the purest form of measured efficiency.

Unlike commodities or manufactured goods, a service is value created and consumed in the same moment.

Because of this, the entire economic signal of a service is captured in the difference between inputs consumed and value delivered.

That difference—the profit margin—is the expansion of the money supply.

Every time a provider delivers more value than they consume in inputs, the system expands proportionally.

Efficiency, innovation, and competence become the literal engines of monetary creation.

The net growth of the money supply equals the sum of all positive margins across the economy.

Each verified service transaction automatically measures the gap between consumption (inputs purchased) and production (outputs sold).

Aggregate that across the economy, and you have a continuous real-time metric of productivity.

No speculation, no policy lag—just a self-balancing system that grows only as fast as civilization becomes more effective at creating value.

Services, therefore, are not a secondary category of production—they are the clearest mirror of how well a society turns knowledge, skill, and organization into surplus.

Every improvement in process, every hour saved, every innovation that yields more with less, literally expands the economy’s usable liquidity.

3.4 — Example: Aggregate Money Supply Growth Through a Production Chain

To understand how the Clearinghouse ties money supply directly to real production, consider a simple example — a tree transformed into furniture through a sequence of tradeable events. Each step mints and destroys currency in response to verified creation and consumption, ensuring that the total money supply expands only as new value is added.

1. Harvesting the Tree

A logger cuts down a tree and sells the raw timber to a sawmill for $40.

- The logger’s labor is the verified input; the delivery of logs is a verified output.

- The Clearinghouse mints $40 in new CHUs for the sale and destroys $40 from the sawmill’s balance.

At this point, the net money supply has increased by $40 and the logs are now part of the productive inventory.

2. Milling the Lumber

The sawmill cuts and dries the wood, creating finished lumber worth $100.

- The process consumes $40 worth of logs plus $5 in energy and $5 labor costs.

- The mill sells the lumber for $100; the Clearinghouse mints $100 and burns the buyer’s $100.

Because $45 in verified inputs were consumed, the net increase in circulating CHUs is +$55, for a total increase of $95. The $5 in energy was physically destroyed in the process. Of the $5 that went to labor, $2 of that might be physically destroyed as food or gas, $3 might go to other goods and services in the economy and so on.

3. Manufacturing the Furniture

A carpenter buys the $100 of lumber and crafts a table, selling it for $200.

- Inputs: $100 in lumber, $90 labor, $10 hardware.

When the carpenter sells the furniture, the Clearinghouse mints $200 and destroys $200 from the buyer’s balance. If you apply the same approximation to the income of the lumberjack and the carpenter then of that final $200 value, maybe $58 was physically consumed as food and energy, the other $142 continues to propagate through the economy in the same fashion while the table now represents $200 in potential value that could be restored if put of for sale.

4. Resale and Depreciation

A consumer later sells the used table at a garage sale for $100.

The resale event mints $100 and burns $10, but since the furniture has depreciated, the total market valuation is now lower by $100.

The economy’s money supply contracts naturally by that amount — not through policy, but through real market behavior.

You could extend this to when the table is sold as firewood for $10, another $10 is minted and burned, and then the table is physically burned. The market value has now been reduced by $190, if the seller then bought and ate a $10 hamburger with the proceeds, all original value would be consumed.

5. Durable vs Consumable, the Value Cascade

At each stage in the process of production some of the value will be destroyed as consumables like food, gas, electricity, healthcare, etc, but some value with be transformed into durable goods such as houses, cars, factories, equipment, etc, that represent potential value outside the system that could always be sold back into the system at which point another minting and burning process would occur as normal. In this way, the system is agnostic to the origin of goods, whether it’s new or used cars, clothes, houses, etc. If an item is being sold in the market, then it represents tangible, available value which needs liquidity to measure.

4 — The Clearinghouse Architecture

4.1 How value is verified

Every act of production generates a measurable artifact: a crop yield, a manufactured good, a service delivered, or an hour of labor performed.

Every exchange in the Clearinghouse follows the same rule:

Currency is minted when verified value is sold and destroyed when that value is consumed.

This applies uniformly to:

- Labor (verified by time or payroll logs),

- Commodities (verified by COAs or quantity measurements),

- Manufactured goods (verified by delivery or acceptance), and

- Services (verified by completion or contract).

Each verified trade event simultaneously increases and decreases the money supply by equal amounts—minting for the seller and burning for the buyer.

Because every transaction represents both a contribution and a consumption, the total supply of currency reflects the living state of production itself.

4.2 Tradeable events vs. transfers

Only tradeable events — real exchanges of value — mint or destroy currency.

Transfers, such as gifts, taxes, or inheritance, simply move existing CHUs between accounts.

This distinction keeps the money supply perfectly neutral.

Consumption shrinks it, production expands it, and transfers merely shuffle ownership.

4.3 Labor, rents, and durability

- Labor: Each paycheck is a verified production event; workers mint their own wages as they perform work.

- Durable assets: A house, machine, or piece of infrastructure generates value repeatedly. Every rental period mints new CHUs proportional to the ongoing service it provides.

- Consumables: Fuel, food, and raw materials mint currency once, then vanish when used.

In this way, time itself becomes a factor in monetary creation — durability and productivity are rewarded automatically.

4.4 — The Clearinghouse as Payment Processor and Marketplace

Despite its theoretical implications, the Clearinghouse would look and feel less like a central bank and more like a next-generation payment processor—part Amazon, part PayPal, part ERP system.

Its visible layer is simply a transactional platform where producers list goods or services, buyers make purchases, and every sale automatically updates the shared economic ledger.

To participants, it behaves like any familiar e-commerce or payroll portal.

Producers upload listings, buyers check out, and each transaction automatically handles the minting and destruction of CHUs in the background.

Employers process payroll through the same interface, using verified time logs or salary schedules as labor events.

Retailers integrate through standard POS systems—customers pay as usual, and the Clearinghouse API reconciles the ledger instantly.

POS terminals, online platforms, and banks can all integrate through open APIs, making the Clearinghouse a software layer that upgrades how money and accounting talk to each other.

Users wouldn’t need to learn economics—they’d just use a cleaner, cheaper, more transparent version of the systems they already trust.

This design ensures the most radical monetary reform in centuries can emerge as a user-experience upgrade, not a political upheaval.

By embedding verified value creation directly into the act of commerce, the Clearinghouse makes the invisible structure of the economy both visible and self-correcting.

5 — Monetary Flows and the New Balance Sheet

5.1 Minting and burning

When two parties exchange verified value, the Clearinghouse simultaneously:

- mints CHUs equal to the sale value,

- burns CHUs from the buyer’s account.

The total supply adjusts in real time with productive activity.

No central planner estimates; the economy regulates itself through its own transactions.

5.2 Liquidity without debt

Because CHUs originate from production rather than loans, liquidity no longer depends on outstanding debt.

People can repay or save without draining the money supply.

Recessions caused by “credit crunches” simply stop happening.

5.3 Accounting identity

In aggregate:

Money Supply = Sum of Verified Production − Sum of Consumption

That’s the first monetary equation where both sides describe physical reality.

6 — Integration with Existing Fiat Systems

6.1 The USD–CHU bridge

In transition, CHUs coexist with dollars.

Employers or buyers purchase CHUs with USD from the Clearinghouse exchange (1 CHU = 1 USD parity).

Those dollars enter a reserve pool; CHUs circulate within the real economy.

When someone redeems CHUs for USD, the Clearinghouse releases dollars from the reserve and burns the redeemed CHUs.

From an accounting perspective it’s a foreign-exchange swap, not money creation.

The supply of USD in reserves always equals the number of redeemable CHUs.

6.2 The Federal Reserve as liquidity window

The Fed can operate a production-backed QE:

Instead of buying Treasuries or mortgage bonds, it buys CHUs — proofs of completed output — at par.

Each purchase injects USD directly into producers’ hands while giving the Fed an asset fully backed by real goods.

Later, it can sell or cancel CHUs to contract liquidity.

This keeps monetary policy simple: inject dollars after production, withdraw after consumption.

6.3 Why it’s not inflationary

Traditional QE adds reserves without adding output, so prices chase scarce goods.

CHU-QE adds liquidity only when goods already exist.

Each new dollar corresponds to finished production; every redemption retires both the CHU and its USD backing.

The result is price stability by design.

7 — Government and the New Fiscal Role

The government no longer functions as an emergency liquidity pump.

Its spending is just another verified purchase that mints CHUs.

Taxes are pure transfers: moving currency from citizens to the state without changing supply.

Policy shifts from guessing how much to print to choosing what to buy.

Public investment becomes a production event — roads, research, and defense all mint money through their real outputs.

Fiscal and monetary policy finally occupy the same ledger.

7.1 — Regulation as Measurement, Not Control

In most economic systems, “regulation” implies active interference: governments levy taxes, impose price controls, or subsidize industries in an attempt to correct the market’s behavior.

These interventions often distort incentives, breed inefficiency, or create political dependence.

But in the Clearinghouse model, regulation takes on a fundamentally different meaning.

The government no longer extracts value from the system—it simply defines the rules of measurement that ensure every transaction is genuine.

The state’s role is analogous to a referee, not a participant.

It does not take profit, set prices, or dictate production targets.

Instead, it maintains the integrity of the verification infrastructure—the “calibration” of the economy.

Its function is to guarantee that every reported unit of production corresponds to something real: labor performed, goods delivered, or services rendered.

This transforms regulation from an act of control into an act of truth enforcement.

1. The Regulatory Role as Infrastructure

The government oversees:

- Verification Standards: Licensing labs, auditors, or digital oracles that confirm production events.

- Identity and Security: Ensuring participants are legitimate and protected against fraud.

- Ledger Integrity: Maintaining the protocols that handle minting, burning, and recordkeeping.

These are not profit-seeking activities. They are public goods—shared utilities, like weights and measures, without which markets cannot function.

2. The End of Fiscal Distortion

Because the government does not mint money for itself or extract rents from the system, it cannot create inflationary or deflationary pressure through spending.

When it purchases goods or services, those are normal tradeable events like any other: money is minted for the seller, burned from the buyer, and the government acts merely as a participant, not a privileged issuer.

In this sense, the Clearinghouse internalizes fiscal discipline.

There is no need to raise or lower interest rates, no need for stimulus or austerity; the flow of liquidity follows the natural rhythm of production and consumption.

3. A True Market Economy

Under this structure, the “free market” finally functions as it is often idealized:

prices reflect real supply and demand, not monetary manipulation or speculative distortion.

Government’s role is neither capitalist nor socialist—it is metrological.

It defines the standards of value, verifies adherence, and leaves the outcomes to collective human judgment.

This is what I mean by regulating markets.

Not in the sense of steering them, but in the sense of keeping them honest.

The Clearinghouse provides the structure in which markets can operate without fraud, excess leverage, or hidden dilution of value.

The government’s presence is constant but neutral—an arbiter of reality, not a competitor for profit.

8 — Macroeconomic Effects

8.1 Self-stabilizing liquidity

In the Clearinghouse world, liquidity grows wherever productivity grows and shrinks wherever consumption occurs.

Recessions caused by “money shortages” vanish.

There can still be real slowdowns—poor harvests, broken supply chains—but never a liquidity drought caused by bookkeeping.

Money ceases to be a hostage of bank lending cycles.

Production itself becomes the heartbeat of currency creation.

That means expansions are earned, not borrowed.

8.2 Reversing the Cantillon effect

Today, new money enters through the financial core and leaks outward—first to asset owners, last to workers.

The Clearinghouse reverses that.

New currency appears at the edges—factories, farms, service counters—where real work happens.

It flows inward toward savers and investors only after circulating through production.

The distribution bias that fuels inequality simply disappears.

8.3 Ending the debt spiral

Because CHUs aren’t created as liabilities, the economy can pay off all legacy debt without suffocating liquidity.

USD debt can be retired gradually; CHUs expand naturally to replace it.

In the limit, one dollar could theoretically clear all remaining debts if velocity were high enough—because the CHU layer keeps real trade alive as the debt layer evaporates.

8.4 Real growth without bubbles

Asset bubbles rely on excess liquidity disconnected from real output.

In the Clearinghouse, that disconnection can’t occur.

Money supply follows production, so speculation without output starves itself of fuel.

Capital flows to where things are actually made.

8.6 — Fraud Resistance and Market Integrity

The Clearinghouse structure inherently dissuades fraud and manipulation, not through surveillance or punishment, but through economic futility.

In traditional financial systems, bad actors can create artificial liquidity by fabricating transactions, inflating valuations, or exploiting leverage.

In the Clearinghouse model, those paths simply lead nowhere, because currency creation is tied to verified exchange and destroyed at equal value.

1. Collusion Creates No Net Gain

Two parties attempting to “trade” fake goods or services accomplish nothing.

When one sells a product for $100, the Clearinghouse mints $100 to the seller and destroys $100 from the buyer.

If they are the same person, or colluding entities, no new money enters the system—only a circular transfer of identical value.

Unlike debt-financed systems where credit creation can inflate paper wealth, here every minting event must correspond to actual consumption by an independent participant.

Fraud becomes self-canceling.

2. Unwanted or Worthless Products Don’t Mint Money

A product has no monetary effect until it is sold.

An undesirable or excessive item—whether poor-quality goods, unnecessary output, or speculative waste—cannot generate liquidity because there is no willing buyer.

If demand doesn’t exist, the tradeable event never registers and no CHUs are minted.

The system therefore rejects inefficiency by omission.

Value is not claimed by declaration; it is earned through acceptance.

3. Verification Anchors Prevent Fabrication

For high-value or variable goods, verification steps (e.g., Certificates of Analysis, delivery confirmations, or payroll logs) create independent proof of work or product.

A fraudulent claim must bypass multiple layers of consensus: the verifier, the counterparty, and the ledger itself.

Because the state and the Clearinghouse only record completed and validated exchanges, they have nothing to “approve” until other humans have already agreed that value was transferred.

4. Incentives Align Toward Authentic Production

Every incentive in the Clearinghouse architecture points toward genuine creation.

Falsifying production earns nothing; overproducing earns nothing; hoarding earns nothing.

The only reliable way to gain liquidity is to provide something that others freely choose to pay for.

This restores moral symmetry to economics: reward follows contribution, not manipulation.

5. Economic Immunity Through Structure

The brilliance of the Clearinghouse model is that it doesn’t need to police intent—it makes deceit economically sterile.

Fraud, collusion, and empty speculation are still possible, but they are unprofitable by design.

The system’s equilibrium rests not on trust in individuals, but on the structure of verified trade itself.

8.7 — Real Asset Valuation and Periodic Value Creation

Durable assets—like homes, machines, or energy systems—represent stored productive capacity.

They don’t just exist; they generate value over time.

The Clearinghouse recognizes this by minting new currency not when an asset is built or purchased, but when its productive potential is realized through verified use—such as rent, energy output, or service delivery.

This approach distinguishes between asset value (what the thing is worth if sold) and periodic value creation (what it produces each cycle).

1. Housing Example: Ongoing Value vs. Stored Capital

Asset: A 3-bedroom home valued at $240,000.

Monthly rent: $1,500.

Clearinghouse Dynamics

- The homeowner holds an asset valued at $240,000—this is stored productive capacity.

- Each month, when a tenant pays $1,500 in rent, a verified trade event occurs:

- $1,500 CHUs are minted for the landlord (production of shelter).

- $1,500 CHUs are burned from the tenant (consumption of shelter).

- $1,500 CHUs are minted for the landlord (production of shelter).

This represents new value created that month: the service of habitation, derived from the home’s existence and maintenance.

No inflation or speculative multiplication occurs; the currency appears and disappears in step with actual utility.

Annualized Production

Over 12 months, the home generates:

- $18,000 in verified production.

- This corresponds to 7.5% of the asset’s value being realized as economic activity per year.

The home’s value itself remains stable (barring depreciation or appreciation), but the service it provides—shelter—is continuously tokenized and measured through rent.

That recurring flow constitutes the real yield of the asset within the economy.

Depreciation and Maintenance

If the home requires $3,000 in annual maintenance, those transactions (materials, labor) are separate verifiable events.

They burn a portion of the landlord’s income while minting liquidity for the suppliers and contractors.

The system automatically accounts for depreciation and upkeep through these continuous flows—no arbitrary accounting adjustments required.

2. Solar Panels: Periodic Energy Production as Verified Output

Asset: A rooftop solar array valued at $30,000.

Annual electricity generation: 10,000 kWh.

Local retail energy value: $0.15 per kWh.

Clearinghouse Dynamics

Each kWh represents a verified, measurable unit of output.

When energy is sold to the grid or credited to a household, the Clearinghouse logs the transaction:

- Seller (panel owner): earns 10,000 × $0.15 = $1,500/year in verified production.

- Buyer (utility or consumer): consumes $1,500 worth of energy, which triggers a burn of equal CHUs.

Annualized Production

- The solar panels generate $1,500 per year of verified production, or 5% of their total value annually.

- If the owner uses the energy personally, the Clearinghouse can log it as an internal consumption credit, maintaining accounting parity while no liquidity changes hands.

Lifecycle Value

Over a 20-year lifespan:

- Total verified production = $30,000.

- This equals the original asset value—confirming that its economic contribution matches its embodied cost across its lifetime.

In effect, the panels repay their existence through verified use.

After they cease functioning, they no longer generate production events, and their accounting value naturally falls to zero.

8.8 Emergent Interest and the Natural Rate of Return

In conventional monetary systems, interest rates are policy tools designed to manage liquidity and incentivize lending. Within the Clearinghouse framework, however, interest arises naturally and independently of central intervention. It reflects the real cost of holding potential energy—unspent CHU—against the physical entropy of the system and the opportunity cost of forgone production.

Identical, Fully Collateralized Units

Each CHU is an identical, fully verified claim on completed production. Lending CHU does not involve credit creation or speculative leverage; it merely transfers the right to redeem that stored value. The lender’s reward is the borrower’s compensation for deferring immediate consumption, not a return extracted from monetary expansion.

Entropy and Opportunity as the Basis for Interest

All goods and services underlying CHU ultimately decay, depreciate, or become obsolete. Holding CHU indefinitely therefore implies accepting a gradual erosion of the real value it represents, as the physical stock of order it claims continues to age and require maintenance.

Consequently, the natural interest rate (rnatural) tends to approximate the sum of two measurable components:

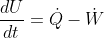

![]()

- ΔVdecay: the average rate at which real capital depreciates or inventories lose utility.

- ΔVopportunity: the additional value that could have been earned by reallocating the same CHU into new production.

This formulation anchors the time value of money in the physical world, not in policy or expectation. Time itself—through entropy—becomes the universal interest clock.

Lending as a Market Function

In this model, lending remains a voluntary market process:

- Borrowers pledge verified collateral or production plans, subject to the same COA-based verification as any other good.

- Lenders allocate idle CHU to productive actors, receiving repayment plus a negotiated share of future verified production.

- The Clearinghouse records these contracts and validates repayments as standard transfers, without altering the monetary base.

Because all CHU are equivalent and fully collateralized, there is no systemic credit risk or fractional reserve effect. The financial sector’s role shifts from money creation to curation of productive opportunity—assessing projects, aggregating capital, and distributing verified profits.

Interest as a Signal of Efficiency

Interest in this context becomes a thermodynamic measure of efficiency:

- A high system-wide rate signals scarce liquidity relative to viable production—energy trapped as idle potential.

- A low rate indicates efficient circulation and minimal idle capacity.

- Over time, as technology and durability improve, rnatural converges toward the mean physical depreciation rate of civilization’s total capital stock—typically estimated near 2–3 % annually.

Thus, the economy self-regulates: interest reflects the balance between stored potential and active transformation, not monetary scarcity.

Interest as the Price of Order

In philosophical terms, interest in the Clearinghouse system is no longer a reward for risk, but the price of maintaining order against entropy. It quantifies the tension between the urge to preserve and the necessity to transform—the heartbeat of a living economy.

By anchoring interest in measurable physical decay rather than monetary policy, the Clearinghouse transforms finance from an exercise in speculation into one of stewardship: allocating energy, attention, and time where they yield the most enduring structure.

9 — Transition Strategy

9.1 Phase 1: Payroll and commodities

The simplest on-ramp is payroll.

Employers route wages through the Clearinghouse (as they already do via payroll processors).

Each paycheck mints CHUs verified by labor performed.

At the same time, commodity producers (steel, corn, energy) join via automated COA links.

That single step could anchor more than half of GDP in production-backed money.

9.2 Phase 2: Retail and services

Retailers adopt CHU payments much like they once adopted credit cards—because it’s cheaper, faster, and more stable.

Service industries follow, minting CHUs for verified time or output.

Consumers can pay in CHUs or redeem USD on the spot.

9.3 Phase 3: Integration with fiscal policy

The Treasury declares parity (1 CHU = 1 USD) and accepts CHUs for taxes.

The Fed establishes the CHU liquidity window, allowing two-way convertibility.

From that point, CHU becomes a second base layer of money—coequal with dollars but anchored to production instead of debt.

9.4 Phase 4: Gradual dominance

As more transactions occur in CHU, the USD layer becomes an external settlement currency.

Debt instruments are phased out naturally as CHU liquidity provides the same working capital without interest.

Within a decade, the majority of domestic trade could operate entirely on production-backed money, with no coercion or disruption.

10 — Global and Geopolitical Context

10.1 Trade parity

Between nations, CHU functions like a commodity-backed reserve.

Countries can exchange CHUs directly or via existing FX markets.

A nation’s currency strength now reflects its productive capacity, not its debt appetite.

Trade imbalances still exist but become self-limiting:

persistent importers run down their CHUs and must produce or offer value to replenish them.

Persistent exporters accumulate CHUs representing tangible global claims on real goods.

10.2 Reserve systems and central banks

Central banks could hold CHUs the same way they hold gold or foreign bonds.

Unlike Treasuries, CHUs never default—they already represent completed work.

They become the new risk-free asset class.

The global reserve architecture shifts from debt-backed fiat to production-backed credit.

10.3 Compatibility with digital finance

The Clearinghouse ledger is digital-native.

It can operate on distributed infrastructure or conventional databases.

Every transaction is cryptographically signed, traceable, and auditable.

But unlike cryptocurrency, it’s anchored in physical verification rather than scarcity myths.

It’s the missing link between blockchain transparency and real-world value.

10.4 — Balanced Trade Through Reciprocal Value Creation

In the modern world, international trade is distorted by the asymmetry between debt-based money creation and real production.

Nations that issue reserve currencies can import goods indefinitely by exporting financial assets — bonds, securities, and promises — while productive nations must continually run surpluses to accumulate those same paper claims.

The result is chronic imbalance: capital pools in creditor nations, consumption concentrates in debtor nations, and both sides become structurally dependent on maintaining the imbalance.

The Clearinghouse system dissolves that dynamic by linking money creation directly to verified production.

Each CHU minted anywhere in the world represents value already created, not credit extended.

This turns trade from a game of capital flows into one of reciprocal production.

1. Real Output, Not Financial Claims

Under the Clearinghouse model, a nation can only inject liquidity into its economy by producing verifiable value—whether in goods, energy, services, or intellectual property.

When it trades internationally, its exports represent genuine, extinguished production events.

Imports must be paid for with CHUs backed by equally verified domestic output.

In this way, trade automatically self-balances over time.

A persistent trade deficit becomes impossible to sustain indefinitely because a country cannot mint new CHUs without producing.

Likewise, a trade surplus naturally levels off as foreign CHUs accumulate — claims on real production that can only be redeemed for actual goods or services, not speculative paper.

2. Exchange Rate as a Reflection of Productivity

Exchange rates between nations’ Clearinghouse currencies adjust based on aggregate productive capacity, not speculative capital flows.

A nation that innovates, improves efficiency, and creates more verified value sees its currency strengthen.

A nation that consumes more than it produces experiences natural depreciation.

No central authority needs to enforce parity — the math of production itself enforces it.

3. Incentive to Produce, Not Hoard

Because every CHU represents completed production, there is no advantage in stockpiling foreign currency.

Holding another nation’s CHUs is equivalent to holding a claim on goods or services that could be consumed or reinvested.

This encourages reinvestment of trade surpluses into productive activity — factories, infrastructure, or technology — rather than passive reserve accumulation.

Conversely, deficit nations must increase domestic production or innovation to restore parity, not simply borrow to delay correction.

4. The End of “Race to the Bottom” Dynamics

Debt-based systems encourage undercutting—currency devaluation, wage suppression, and environmental shortcuts—to stay competitive.

The Clearinghouse flips the incentive structure: quality, durability, and efficiency become the paths to growth.

The more authentic value a nation’s industries generate, the more liquidity its economy receives.

Sustainability and productivity are rewarded directly; exploitation and waste contract the money supply.

5. Trade as a Collaborative, Not Zero-Sum, System

When every country’s money creation depends on verified production, global trade becomes a network of complementary specializations rather than competing deficits.

Nations exchange what they are best at producing, each expanding their internal liquidity through their own productive contributions.

Mutual gain replaces mercantilist accumulation as the natural equilibrium.

10.5 — Global Reserve Implications

For the past century, global trade and finance have revolved around a single asymmetry: the dominance of the reserve currency.

Since the Bretton Woods system, the U.S. dollar has served as the medium of international settlement, not because it uniquely represents value, but because it uniquely issues debt that others accept as value.

This arrangement has conferred immense advantages on issuer nations while trapping the rest of the world in a cycle of dependency, volatility, and forced savings.

The Clearinghouse framework provides a path out of that imbalance by introducing a neutral, production-backed reserve asset—a unit that represents completed work rather than sovereign debt.

Because each CHU (or its national equivalent) is minted only after verified production, it carries intrinsic, non-political credibility.

A CHU from any participating economy means the same thing everywhere: real value was created.

1. A Post-Dollar Reserve Standard

Under the Clearinghouse model, reserve holdings would gradually shift from debt instruments (like Treasuries) to verifiable production credits.

Central banks could hold baskets of CHUs originating from multiple nations, diversified by sector or region.

These holdings would not generate interest through debt repayment but through global liquidity participation—redeemable for goods, services, or production rights across the network.

This would end the “exorbitant privilege” that allows reserve-currency issuers to export inflation and import goods indefinitely.

A nation’s global influence would once again match its productive capacity, not its financial leverage.

2. Intrinsic Stability

Debt-based reserves fluctuate with interest rates, political risk, and speculation.

Production-backed reserves fluctuate only with real global output.

A downturn in one region’s productivity automatically reduces its CHU issuance, tightening liquidity organically without currency collapse or capital flight.

The result is a system that adjusts smoothly to economic reality rather than amplifying every shock.

3. Transparent and Auditable

Every CHU is linked to a verified production event—labor performed, commodity processed, service rendered.

Unlike gold, which is finite and inert, or fiat, which is infinite and abstract, CHUs are finite within each production cycle and fully traceable.

A global reserve ledger could show precisely how much of the world’s liquidity came from agriculture, energy, technology, or services—turning macroeconomics into a transparent data layer rather than a guessing game.

4. Gradual Adoption

Transition need not be abrupt.

Governments could begin by holding small CHU portfolios as diversification, just as they now hold SDRs or gold.

As confidence builds and convertibility spreads, CHUs could form the backbone of a multi-polar reserve system, with each nation’s productive contribution proportionally represented.

In time, debt-based reserves would shrink naturally as trade settlement and savings shift toward verified-value instruments.

5. End of Global Imbalances

With CHUs serving as a neutral settlement medium, there is no incentive to hoard foreign reserves or manipulate exchange rates.

Nations trade goods for goods, services for services, and liquidity arises directly from mutual production.

Global finance becomes a distributed clearing network—a world Clearinghouse—where money supply, trade flows, and reserves all speak the same language: real output.

11 — Thermodynamic Foundations of the Clearinghouse System

The Clearinghouse System can be understood as a thermodynamic engine operating within the human economy.

In this framework, currency (CHU) represents the kinetic energy of economic motion—value actively circulating through trade—while durable goods, infrastructure, and human skill represent potential energy, the stored capacity to generate future order and productivity.

Transactions are the mechanism by which potential energy is converted into kinetic energy through verified work, and the Clearinghouse serves as the accounting structure that conserves, measures, and regulates that conversion.

1. Energy Equivalence

All economic production is ultimately an act of energy transformation.

Raw materials are ordered, refined, and assembled using labor and fuel, producing goods of lower entropy and higher structure.

In the Clearinghouse framework, each verified trade corresponds to a quantifiable exchange of usable energy—an increase in order somewhere that is matched by an equal consumption elsewhere.

When a product is sold, the system mints new CHUs representing the ordered structure of that good or service.

When that product is later consumed, degraded, or destroyed, an equivalent amount of CHUs is removed from circulation, reflecting the return of that order to entropy.

The money supply thus becomes a direct mirror of the system’s available free energy: every CHU in circulation corresponds to an increment of ordered work currently active in the economy.

2. Potential and Kinetic Energy of Value

- Potential Energy: Stored in assets, machines, infrastructure, and skilled humans—any capacity that can produce verified output.

Houses, factories, solar panels, or even a worker’s training represent low-entropy structures capable of future conversion. - Kinetic Energy: The circulating CHUs themselves—the immediate, measurable exchange of value through verified transactions.

This is the motion of the economy: CHUs moving between agents as production and consumption occur.

Every transaction is a conversion event, turning potential into kinetic, or kinetic back into potential.

A carpenter transforms the potential energy of wood and labor into the kinetic energy of trade when selling a table; the buyer then holds that energy as potential again until the item is used, resold, or destroyed.

3. Entropy, Consumption, and Decay

No production process is perfectly efficient.

Fuel, food, and time are consumed to maintain human and mechanical order.

These consumptive events represent the entropy flow of the economic system—the unavoidable cost of maintaining civilization against disorder.

In the Clearinghouse model, this loss is not hidden behind inflation or debt; it is explicitly recorded as CHUs being burned when goods are consumed or destroyed.

The destruction of money is not punitive—it is the mathematical expression of entropy returning to equilibrium.

When all transactions are recorded in this way, the total currency in circulation becomes a live measure of the system’s energetic vitality.

4. Systemic Equilibrium

Because the Clearinghouse mints and destroys currency only through verified transactions, the total CHU supply adjusts naturally to the system’s energy throughput.

If production expands—more potential energy converted into ordered goods—CHUs increase.

If consumption outpaces creation, CHUs decline.

The system therefore behaves like a closed thermodynamic loop, constantly seeking equilibrium between energy inflows and outflows.

This ensures long-term stability without artificial control: inflation and deflation become thermodynamic effects, not policy outcomes.

Overproduction without buyers creates no new liquidity; overconsumption without production draws down existing liquidity.

Balance emerges automatically, not by decree.

5. A Physically Honest Economy

Under this interpretation, the Clearinghouse is not merely a financial tool but a physical accounting system that obeys the same conservation laws as nature itself.

Every verified act of creation, transformation, or destruction is reflected one-to-one in the monetary layer.

Money, energy, and matter become aligned:

- Nothing can be created without work,

- Nothing can persist without maintenance,

- And nothing can be consumed without consequence.

By grounding economics in thermodynamic law, the Clearinghouse transforms markets from abstract games of speculation into precise reflections of the real physical processes that sustain civilization.

It is an economy that measures truth—the flow of order against the backdrop of entropy—and in doing so, it restores integrity to the concept of value itself.

11.1 — Energetic Model of Monetary Flow

The Clearinghouse can be expressed as a conservation-law system analogous to classical thermodynamics.

In both cases, energy (or value) is neither created nor destroyed except through work.

Only its form changes—from potential (stored order) to kinetic (active trade) and, finally, to entropy (consumption and decay).

1. Fundamental Relation

ΔU = Q – W

Where:

| Symbol | Thermodynamic meaning | Economic analogue in the Clearinghouse |

| ΔU | Change in internal energy of the system | Net change in total verified economic potential (aggregate asset value) |

| Q | Heat absorbed (energy inflow) | Verified production—creation of new ordered goods, services, or infrastructure (minting of CHU) |

| W | Work done by the system on surroundings | Verified consumption, depreciation, or destruction of goods (burning of CHU) |

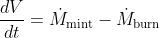

Thus,

is equivalent to

where V is total stored value and M is the circulating CHU supply.

At steady state ( dV/dt = 0 ), production equals consumption and the economy is in thermodynamic equilibrium.

2. State Variables

| Variable | Physical interpretation | Economic counterpart |

| Potential Energy (Uₚ) | Stored capacity for work | Value of durable assets, skills, and infrastructure |

| Kinetic Energy (Uₖ) | Motion of particles | Active circulation of CHU (transaction velocity) |

| Entropy (S) | Disorder or energy dispersion | Irrecoverable consumption, waste, or obsolescence |

| Temperature (T) | Average kinetic energy | Economic “activity level” or turnover rate |

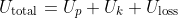

Total system energy (value) is constant:

where Uloss increases irreversibly as entropy rises.

Each arrow represents a verified transaction logged by the Clearinghouse.

Minting corresponds to the downward flow from potential → kinetic; burning corresponds to kinetic → entropic loss.

Maintenance and reinvestment recycle part of the flow back to potential energy through repair, learning, or construction.

4. Conservation and Stability

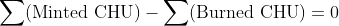

Because every trade event is verified, the Clearinghouse obeys an economic conservation law:

over any closed time interval, except when the system’s total potential energy Up genuinely changes.

Inflation or deflation can therefore only arise from real shifts in production or consumption rates, never from monetary manipulation.

5. Interpretation

- Inflation ⇢ Entropy increase: more value destroyed than created.

- Growth ⇢ Exergy capture: production of new low-entropy structure.

- Equilibrium ⇢ Steady-state civilization: verified production = verified consumption.

The Clearinghouse thus functions as an economic heat engine, transforming potential value into kinetic exchange while continuously measuring and conserving the energy of civilization itself.

11.2 — Exergy and Economic Value

While total free energy represents the full stock of potential value within an economy, only a portion of it can ever be transformed into useful, verifiable work.

That usable portion is exergy—the measure of available energy that can still perform ordered work before entropy renders it inert.

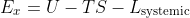

In the Clearinghouse framework, this distinction maps precisely onto the difference between theoretical wealth and real, verified production.

1. Free Energy vs. Exergy

In physical systems, free energy includes all stored energy that could perform work; exergy measures what can actually be used under real conditions.

Friction, waste, and entropy limit the conversion.

In economic terms:

| Physical Quantity | Thermodynamic Definition | Economic Analogue |

| Free Energy (U) | Total stored energy | Total potential value—resources, assets, knowledge, and capacity |

| Exergy (Eₓ) | Portion of energy available for work | Verified, tradeable value—the part that can be sold, exchanged, or utilized |

| Entropy (S) | Unusable energy / disorder | Waste, inefficiency, obsolescence, or corruption that prevents realization of potential value |

Only verified production events—those recorded through the Clearinghouse—constitute exergy.

Idle capacity, unrealized projects, or speculative assets remain free energy: they exist, but they are not yet capable of performing work in the economic sense.

2. Exergy as the Monetary Core

Because CHUs are minted and destroyed only through verified trade, the system measures exergy, not total wealth.

It refuses to assign monetary weight to potential value until that value has been activated through human or mechanical work.

This is what makes the Clearinghouse both self-regulating and thermodynamically honest:

it mints money only when order is created and destroys it when order decays.

Where U is total stored value, TS represents losses to entropy (waste, inefficiency),

and Lsystemic represents logistical or institutional frictions such as transport costs or idle time.

The circulating CHU supply M is proportional to Ex:

The money supply therefore corresponds to the economy’s usable work potential—its exergy—not its theoretical maximum output.

3. Illustrative Examples

- Forestry: A forest’s biomass contains vast chemical energy (free energy), but only the portion that can be harvested, milled, and delivered to market as lumber becomes exergy.

The Clearinghouse mints currency only at that moment of verified delivery.

The uncut trees remain potential value, not circulating liquidity. - Solar Power: A photovoltaic array stores no energy of its own; it continually converts sunlight into usable electricity.

Each kilowatt-hour delivered to the grid represents exergy—measurable, verifiable, and monetizable work.

The panels’ capital cost embodies free energy (embodied order); their daily production expresses exergy.

4. Macroeconomic Implications

By denominating money in exergy rather than potential wealth, the Clearinghouse naturally eliminates inflationary pressure from speculation or idle assets.

Liquidity expands only when society converts potential into useful structure, and it contracts when that structure decays.

The economy thus measures available work capacity rather than promises, and its currency becomes a direct index of civilization’s organized energy.

5. Synthesis

Exergy is the bridge between physics and economics.

It defines value not as possession but as potential realized through verified work.

The Clearinghouse, by monetizing only exergy, turns markets into a real-time map of humanity’s effective order—the portion of our collective energy still capable of shaping the world.

12 — Conclusion: From Promises to Proof

Every civilization eventually outgrows its accounting system.

Double-entry bookkeeping made trade possible by tracking obligations.

The Clearinghouse extends that logic to track real outcomes.

Money should not represent a claim on future labor; it should represent labor already done.

When production itself mints currency, the economy finally runs on physical truth instead of financial narrative.

Liquidity no longer needs to be “injected.” It simply exists wherever people are creating value.

This system doesn’t abolish markets or governments.

It just gives both an honest foundation:

- Governments still collect taxes and fund projects.

- Businesses still compete.

- Consumers still choose.

But the bloodstream of the economy—money—finally reflects the living tissue it serves.

The Clearinghouse isn’t utopian.

It’s bookkeeping evolved to its logical conclusion:

A world where every unit of currency has a matching unit of verified production,

and where economic stability is not a political choice,

but a mathematical identity.